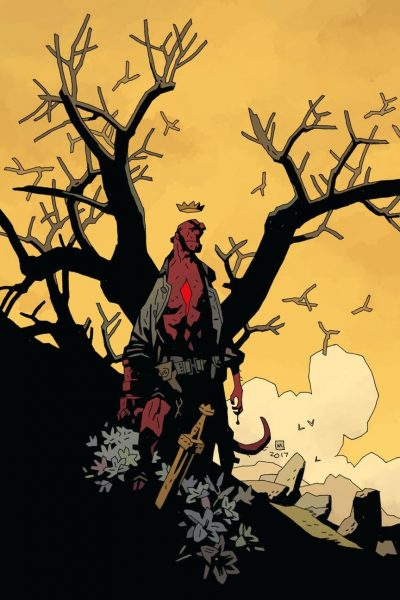

Mike Mignola is unique on our judging panel for Illustration West 59. Not only is he an incredible illustrator with his own distinct, inspiring artistic style, but he also is the creator of a very popular comic book character that has spread across the pop culture landscape not just in books, but also in three live-action motion pictures, and two animated films.

Mike Mignola is unique on our judging panel for Illustration West 59. Not only is he an incredible illustrator with his own distinct, inspiring artistic style, but he also is the creator of a very popular comic book character that has spread across the pop culture landscape not just in books, but also in three live-action motion pictures, and two animated films.

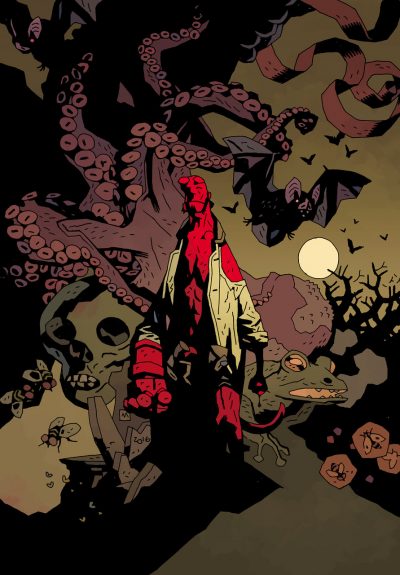

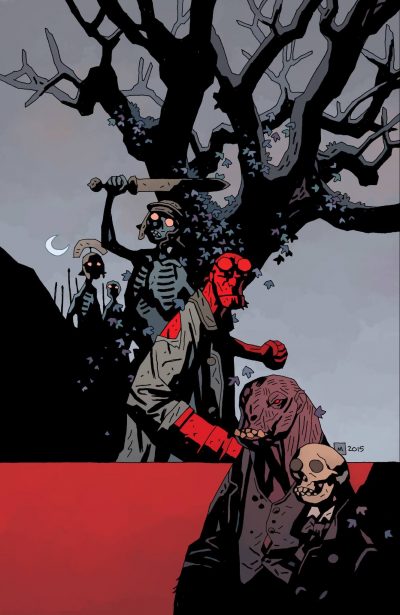

Mike’s understanding of light and shadow in his work is mesmerizing. His ability to create mood and drama with the proper placement of stark shapes may look simple when one looks at a finished piece, but most artists know how difficult that can be as it not only requires an expert knowledge of lighting, but also an expert knowledge of composition. This is certainly impressive when just dealing with a solitary illustration, but it is compounded by the fact that Mignola is creating narrative stories with his art. That means he has to plan sequential drawings out with consistency, with the goal of storytelling in mind.

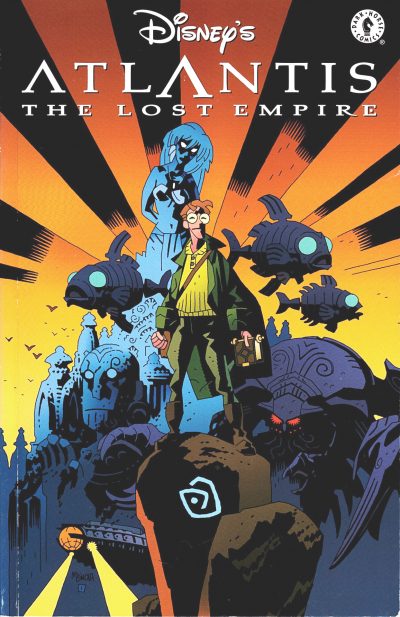

While knowing of Mike’s work in comics, it wasn’t until the late ‘90s when my world intersected with his. I was a young guy in a starting position at Disney Feature Animation when they were developing Atlantis: The Lost Empire in the Mignola artistic style. What a pleasure it was over those years to see the art on the walls that the visual development artists were putting together in Mike’s style side-by-side with Mike’s own concepts for the film. The work was just so epic in every sense of the word, and what an amazing tribute to a solitary artist to have Disney be interested in emulating his look.

With great pleasure, I was able to ask Mike a few things about his artistic style, the business of being Hellboy’s creator, and even a little about Disney’s Atlantis with the hope that this interview offers you some creative encouragement. We are so pleased that Mike will be reviewing everyone’s art submitted by the October 31st deadline of this year’s Illustration West competition!

Chad Frye

Illustration West 59 Show Chair

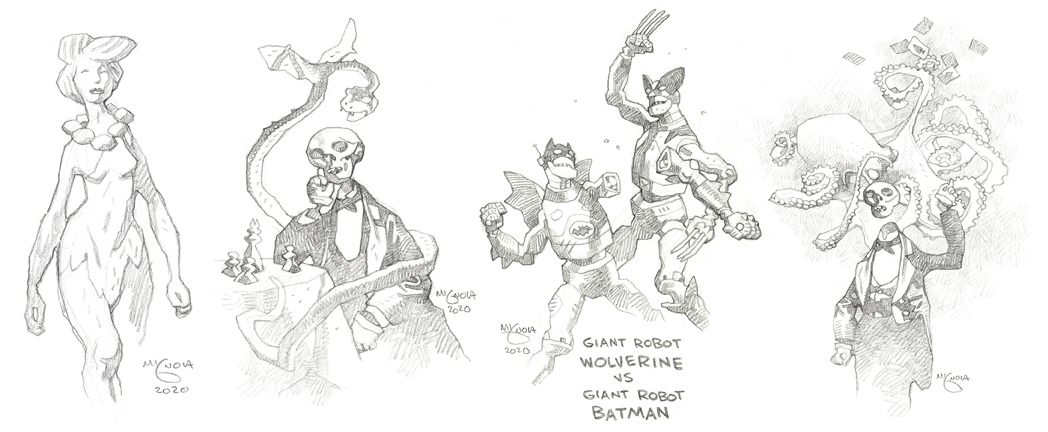

Let’s get right to it – over on your Instagram account (@ArtOfMM), you are a posting fiend with new sketches, drawings, and paintings going up almost daily. These are not just Hellboy pieces one might expect, but we’re seeing your versions of Kermit the Frog, Mr. Peanut, Maurice Sendak characters, Frankenberry, gaming characters, and so much more! Much of this art you auction off on eBay for charity. What has been your inspiration for this daily burst of creativity?

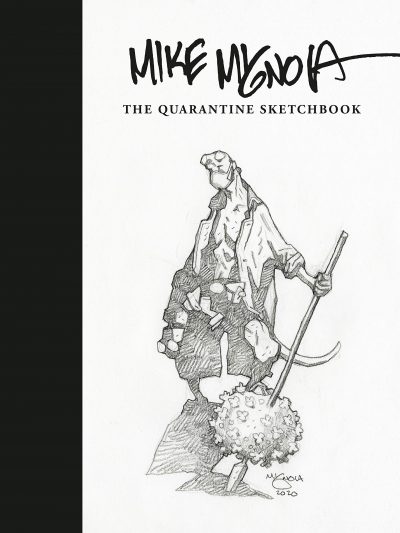

The sketches started as a way to just distract myself from what was going on in the world as the COVID-19 thing started to take off – a way to entertain myself and anybody who was following me on Facebook. It was just fun to draw a whole lot of stuff I’d never thought to draw before. I think it started (I don’t know why) with my take on The Flintstones. There was no planning at all – it just happened, and then it all snowballed from there. I was drawing like a fiend – maybe as many twenty sketches a day. Of course, not all were good enough to post – a lot went into the garbage – but I quickly got addicted to doing them. Posting them and getting the reaction from people right away was not something you get when you’re drawing for publication. As they piled up, my wife and I started talking about what to do with them.

The sketches started as a way to just distract myself from what was going on in the world as the COVID-19 thing started to take off – a way to entertain myself and anybody who was following me on Facebook. It was just fun to draw a whole lot of stuff I’d never thought to draw before. I think it started (I don’t know why) with my take on The Flintstones. There was no planning at all – it just happened, and then it all snowballed from there. I was drawing like a fiend – maybe as many twenty sketches a day. Of course, not all were good enough to post – a lot went into the garbage – but I quickly got addicted to doing them. Posting them and getting the reaction from people right away was not something you get when you’re drawing for publication. As they piled up, my wife and I started talking about what to do with them.

As the world was pretty much falling apart, we thought doing something for charity would be a good idea. My wife, Christine, had been following José Andrés and his World Central Kitchen, and we both thought that with what was going on, and the superhuman work he was doing to feed people, if there was something we could do to help with that it would be perfect. So, I was just doing the drawings to keep myself from going crazy, but it was Christine who turned what I was doing into something more. Eventually Dark Horse will be publishing a book of the sketches with all the proceeds going to World Central Kitchen. Unfortunately, not everyone has given us permission to use their characters. Disappointing, but not a surprise – but there was still more than enough pieces to make (I think) a very nice book.

Let’s dive a little into the development of little Mikey becoming the Mike Mignola we know and love. There is a lot of darkness in the work you produce today. Did Mom and Dad used to worry over dark, brooding Crayola pictures they would find around the house when you were a kid?

First off, let’s never refer to “little Mikey” again, but no, I don’t remember anyone being all that concerned. And it’s not like I was sitting there all day drawing ax murderers – I was drawing all kinds of stuff. In fact, I don’t recall drawing a lot of horror as a kid. That stuff would come later, but all I ever did was draw – inspired by books and comics. I was never good at anything else. My father’s main concern was how I was going to make a living. All he knew about artists was that they starved, or they got a teaching job. I’m very happy that he lived long enough to see that I didn’t starve.

I find that many cartoonists come to their profession without much exposure to working professionals when they were growing up. Did you know or meet any comic artists when you were a kid that may have encouraged you along  the way?

the way?

My two brothers and I were all into comics, but I didn’t really know anyone outside the family that was into that stuff. The only artists I met were at comic conventions. I probably started going to the local (San Francisco and Berkley) conventions in my late teens. I got to know some of the artists there, showing them my work, and eventually started setting up at those shows. That’s where I met Art Adams, and I guess maybe we inspired/encouraged each other a bit. We were both a couple years from breaking into the business. I think he was the first guy I met that was around my age that was working on breaking into comics, but mostly in the early days, I was doing the stuff on my own. I’ve always been pretty self-motivated.

Were comic books something you always aspired to do? Or were they kind of a fallback to you maybe really wanting to be a medical book illustrator or a police sketch artist or something?

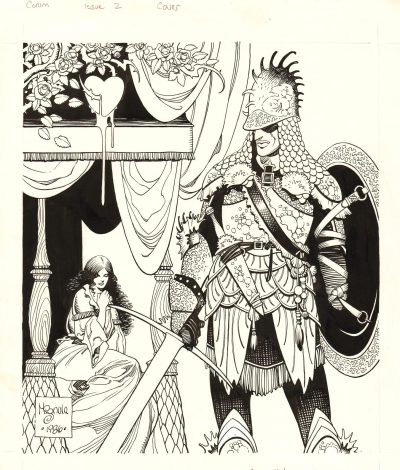

I liked comics as a kid, and through high school I got pretty serious about reading and collecting, but don’t think I ever really thought I’d draw comics. I didn’t try drawing them. I didn’t make up my own comics or anything like that. I thought of myself as much more of an illustrator, but all I really wanted to draw was fantasy stuff. It wasn’t until my last year in art school that I really started to think seriously about where I could go to do that kind of work. I thought eventually I’d like to do covers and pin-up for comics, not draw stories, but didn’t think I could get in the door doing that kind of stuff, so I decided I’d go and become an inker. How hard could that be, right? But it turned out I was a pretty bad inker.

My first editor at Marvel, Al Milgrom, recognized that I was better at drawing than I was at inking and encouraged me to draw pages, but I was too insecure to try – until after a year as an inker, it was clear I was not going anywhere. Then Al gave me a story to draw. I might be one of the few guys working as a professional comic artist who never drew a sample page.

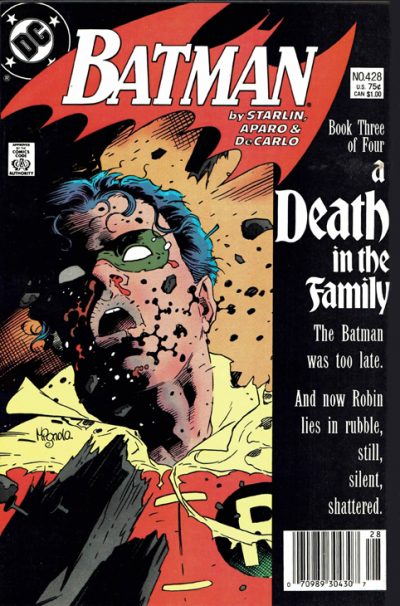

When one hears the name “Mike Mignola,” they instantly think “Hellboy,” a creation that has a very unique artistic look about it. Outside of diehard comic book fans, though, people might not realize you had a whole career drawing other famous superhero comics in a style that might be perceived as more conventional. For instance, I was blown away when I realized you had done the covers for the Batman: Death in the Family series. That one cover of Robin in his hour of distress seared an indelible image on my mind.

When one hears the name “Mike Mignola,” they instantly think “Hellboy,” a creation that has a very unique artistic look about it. Outside of diehard comic book fans, though, people might not realize you had a whole career drawing other famous superhero comics in a style that might be perceived as more conventional. For instance, I was blown away when I realized you had done the covers for the Batman: Death in the Family series. That one cover of Robin in his hour of distress seared an indelible image on my mind.

After that one year as a bad inker, I drew comics for about ten years before creating Hellboy. At first I took whatever jobs I could get. I didn’t really draw like a superhero artist so nobody at Marvel really knew what to do with me – that’s how I ended up drawing Rocket Raccoon. Then onto  The Incredible Hulk – he was a monster, and at the time, he was sort of bouncing around between different fantasy worlds, so that was an okay fit for while. Then I drifted into superheroes, but was never really comfortable there. I did a fantasy series at First Comics, an adaptation of Michael Moorcock’s The Chronicles of Corum, and that suited me better.

The Incredible Hulk – he was a monster, and at the time, he was sort of bouncing around between different fantasy worlds, so that was an okay fit for while. Then I drifted into superheroes, but was never really comfortable there. I did a fantasy series at First Comics, an adaptation of Michael Moorcock’s The Chronicles of Corum, and that suited me better.

In those early years I was just trying to figure out how to draw comics and trying to find material I could get excited about. Even though I wasn’t very good, I did manage to always have work, and the good thing about comics is you have to draw a lot. So I did a lot of bad work, but slowly figured stuff out. That’s why so much of my early work looks nothing like my stuff now – I was just trying to figure out what I was doing.

I work quite a bit in the animation world where with each project, I have to adapt to a new style of drawing. It becomes difficult to know what my own style actually is. After drawing so many other people’s projects in comics, can you speak a little to what it meant to developing your personal drawing style that you are known for today?

Part of the evolution of an artist, I think, is moving beyond your influences and finding yourself. I was influenced by so many artists, and for years I tried to make sense of all those influences. It must be much easier if you’re one of those guys who is just influenced by one or two guys, but by the time I started drawing comics, I’d been influence by so many artists. I didn’t know what I was supposed to be.

I think the turning point for me was when I did Cosmic Odyssey for DC, and spent close to a year looking at Jack Kirby’s work for reference. I had always loved Kirby comics. Fantastic Four and Thor where my favorites as a kid, but I’d never tried to draw like Kirby, and I didn’t try to draw like him on Cosmic Odyssey, but looking at his stuff day in and day out for that long did, I think, liberate me. Rather than try to draw perfect anatomy and stuff like that, I started feeling comfortable to exaggerate and become more impressionistic. Once I started down that road, I started to feel like I was finally finding my own style. It took a while to get there, but at least it felt like I was onto something.

I was a couple years into drawing Hellboy before I really felt I had actually arrived at something. But even now, the style continues to change – more subtle changes than in the old days, but I’m always looking for ways to do things better. I guess, for me at least, that’s what it comes down to – never being entirely satisfied, always looking to improve. And when I say improve, I mean improve for myself with little or no regard for what the fans might want. I’ve been very lucky that the fans (some at least) have followed me all these years.

Your style has clearly inspired many others who have come after you. I think back to when Disney Animation started developing Atlantis: The Lost Empire with your art style in mind before they even brought you on board. What was it like to get that call, realizing they wanted to make a whole movie based on your look?

The Disney call about Atlantis remains one of the strangest, more surreal things in my career. I never would have imagined that anyone at Disney would know my work, let alone want to try to do a film in my style. Even now, looking back, it seems so strange, but it was a fun and exciting thing to be involved with. While the film wasn’t a huge hit for Disney at the time, I now run into a lot of younger artist who LOVE that film. So very proud to have had something to do with it.

And what did I actually do? I did some design work, but the way I remember it is mostly I was just there to throw ideas around. What was crazy is how many of the ideas I tossed out made it into the film – some big ideas like the Atlantean flying machines were just a random thought that I tossed out and it ended up influencing a huge chunk of the movie. Crazy. As far as the actual look of the film, the “Mignola look,” the credit has to go to other artists who had to study my work and figure it out. I couldn’t tell anyone else how to do my style. I just do what I do.

I think every storyteller hopes that people will enjoy what they create, though there isn’t really an expectation in the creator’s mind that their creation will actually become wildly popular. When you were first coming up with Hellboy, did you dare to hope that there could be a life for him beyond your initial story?

When I started Hellboy, I HOPED it would turn into something, but I didn’t really expect it to. What was important to me at the time was to have at least ONE book out there that was entirely made of my stuff – something I’d be able to point to and say, “That’s a pure Mignola comic.” Of course, at the beginning I didn’t have the confidence to script the thing myself. I plotted it and sort of wrote it, and then John Byrne came in to do the final script. He was really just helping me out on the first one because he knew I lacked the confidence, but he knew I should actually be writing it myself.

it would turn into something, but I didn’t really expect it to. What was important to me at the time was to have at least ONE book out there that was entirely made of my stuff – something I’d be able to point to and say, “That’s a pure Mignola comic.” Of course, at the beginning I didn’t have the confidence to script the thing myself. I plotted it and sort of wrote it, and then John Byrne came in to do the final script. He was really just helping me out on the first one because he knew I lacked the confidence, but he knew I should actually be writing it myself.

Then I took over and the next story (Wolves of Saint August) was rough, because actually writing is scary – not something I ever imagined I’d ever do. And then the third one (The Corpse) just flew out of me. It was fun and kind of easy, had humor that I never really realized was going to be part of the thing, and at that point I really did think that if I COULD keep doing the book, at least I’d know HOW to do it. The next full length mini-series (Wake the Devil) is where you see me adding a lot of elements to the book, starting things that aren’t neatly wrapped up at the end. That’s the point where I clearly felt it was okay to start making up a much bigger story, as it looked like Hellboy would be around for a while.

A lot of artists aren’t really prepared for dealing with the normal business side of being an artist, but when one creates something that takes off like Hellboy, the business side of things can rise to a whole other level that’s even more overwhelming to an artist. How have you been able to deal with merchandising, convention appearances, movies, etc., while still trying to create new stories?

I have never wanted to deal with the business end of things. That’s why I was very happy to go to a publisher with Hellboy rather than self-publish. I just want to draw and write the thing. I only got a lawyer when Dark Horse wanted to option Hellboy for a film. When it comes to scary stuff like that, you NEED a lawyer. Beyond that, I’m very lucky to have a wife with a background in business. For years she’s helped out with convention stuff, the website, merchandise, etc. No idea where Hellboy would be had Christine not helped all along the way. Doing this kind of think cannot be a one person operation.

The comic book/graphic novel category has been a part of SILA’s Illustration West competition since 2005, but the cartooning category was only introduced in 2017, and yet comics have been a major art form ever since The Yellow Kid popularized the medium in newspapers in the comic strip Hogan’s Alley back in 1895. It always disappoints me to hear the perception now and then that comics are kids’ stuff, especially when so many talented adult artists pour their all into them. What thoughts might you have about cartooning as an illustration art form?

Comics are here to stay and, by and large, I think it IS recognized as an art form, though maybe still more in other countries than in our own. But over the thirty-five years I’ve been doing this, I have seen a lot of change – a lot of recognition of comics as an important art form even here in America. How many colleges have I spoken to? How many classes specifically about writing and drawing comics? I don’t think there was much of that when I started out way back when. I love seeing what comics have become and where they are going.

Thanks so much for being a part of our Illustration West jury this year, Mike. We look forward to having you review everyone’s work submitted from around the globe!

Very flattered to have been asked and happy to be onboard.