This next judge for Illustration West 59 approaches our business a bit differently from the rest of our judges. Charles Kochman is not an illustrator, but he works with illustrators. More specifically, he hires illustrators in his role as Editorial Director of Abrams ComicArts, and has discovered a large number of creators who have gone on to great success. Do I have you intrigued?

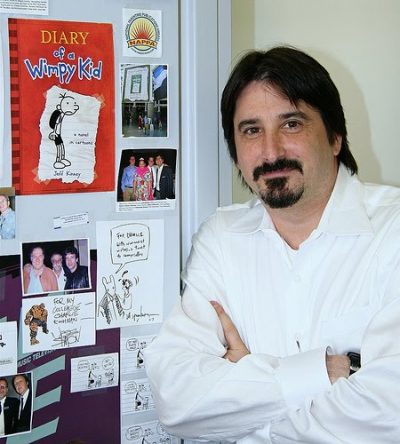

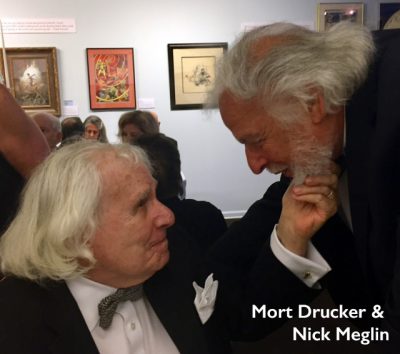

While most well-known as the editor of Jeff Kinney’s The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, Charlie’s experience in publishing spans the past thirty-five years, having produced many beautiful books filled with tremendous stories and art. His knowledge of artists from the past century is evident in the books he has produced, many of them about the trendsetters who most influenced the art of comics. It is because of Charlie’s love for cartoonists that my own path intersected with his twenty years ago at a gathering of the National Cartoonists Society at the World Trade Center, where MAD Magazine editor Nick Meglin first introduced us. We chatted a bit with Mort and Barbara Drucker just before listening to a talk given by the great caricature artist David Levine. That was a pretty. good. day.

I was excited to have a chance to really delve into what it is that Charlie does in his role as an editor. Illustrators know their own part of book creation, but are generally sheltered from the ins and outs of what goes on in the production of a book. My knowledge of the work of editors was certainly illuminated by this discussion with Mr. Kochman. Perhaps you will find it just as informative, too.

Chad Frye

Illustration West 59 Show Chair

Charles, I am thrilled that you agreed to be a judge in this year’s Illustration West competition. Your work as an editor spans art books, children’s novels, picture books, and comics. In fact, when I first met you many years ago, you were an editor for DC Comics. How does a kid from Brooklyn wake up one day and decide he is going to become an editor?

Thanks, Chad. First, let me say it’s an honor to be a judge—thank you for asking me. I am humbled to be considered in the same company as Mike Mignola, C.F. Payne, Justin Gerard, Jason Seiler, Kadir Nelson, Claire Keane, Suzy Hutchinson, and Drew Struzan.

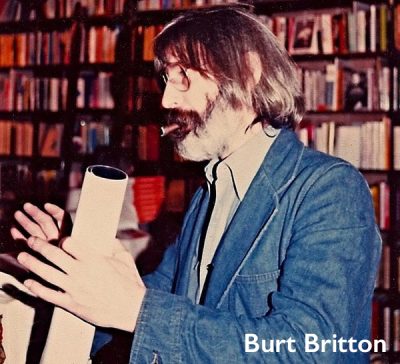

As for your question, it is one I ask myself every day, and have been asking ever since I started in publishing. The short version is I don’t recall wanting to be anything other than an editor. My uncle Burt was a bookseller, most notably at the Strand bookstore here in New York, and after that at Books & Company, which was on Madison Avenue by the Whitney. I feel like I grew up in the basement of the Strand. Burt would pile me with books I had to read, then quiz me on them before I could take home any more. He would show me book

As for your question, it is one I ask myself every day, and have been asking ever since I started in publishing. The short version is I don’t recall wanting to be anything other than an editor. My uncle Burt was a bookseller, most notably at the Strand bookstore here in New York, and after that at Books & Company, which was on Madison Avenue by the Whitney. I feel like I grew up in the basement of the Strand. Burt would pile me with books I had to read, then quiz me on them before I could take home any more. He would show me book  covers and ask what worked about them and what I didn’t like.

covers and ask what worked about them and what I didn’t like.

And he would lay out novels and ask which ones I was more inclined to pick up. Author, title, design, and publishing house all played a role, and he helped me to understand why. I remember Burt taking me to a shelf, and I watched as he removed every other book. He said if I was to be an editor, my job was to not look at what was there, but to focus on the spaces between the books and to see what was missing. That was my training—my Uncle Burt’s boot camp in the basement of the Strand. Immediately after graduating college, I was able to land a job. That was in 1985, and now here I am, thirty-five years later.

What was your first job in this business? Did your educational background play into your chosen career?

My first job in publishing was technically as an intern at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. I was still an undergrad at Brooklyn College, but I was a member of the English Majors Club and became the editor of the student literary journal, which was called riverrun. Our faculty advisor was an incredibly inspiring teacher, Roni Natov, and she recommended me for the internship because she felt it would give me an advantage over the other applicants who were also applying for an entry-level position. She was right.

After I graduated, my first job was as an editorial assistant at PlayValue Books, which was the licensing division of Grosset & Dunlap. That’s where I learned the real mechanics of being an editor. My boss and mentor at the time, Michael Teitelbaum, pretty much taught me everything I know, especially about talent relations. His writers and artists all loved him, and that made a real impression on me.

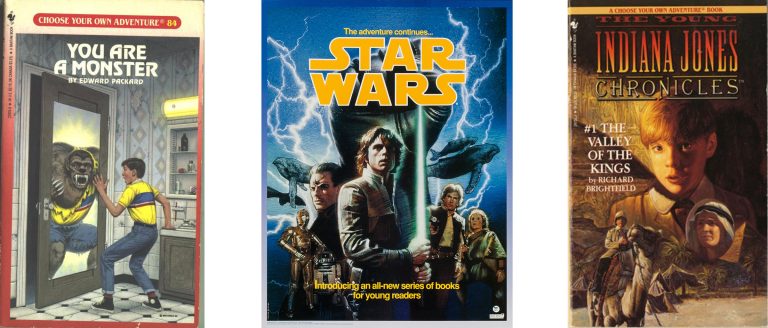

After a couple of years at PlayValue, I went to Bantam Books for Young Readers in 1987, and before long became the editor of the Choose Your Own Adventure series, which is where I really honed my skills. The books were published monthly and were told in second person present, so I learned about point of view and the pressure of a deadline. I also got to develop several ancillary series from scratch, including editing books on major brands like Star Wars and Indiana Jones.

At Bantam, my office was next to Ian Ballantine—the Ian Ballantine, who founded Bantam and Pocket Books and who invented  paperback publishing. I was fortunate to get to know Ian well, and would help him out with various favors (mailing packages, research, that sort of thing). In exchange, Ian would take me to lunch at the Top of the Sixes every month, and that’s when publishing became real to me. He was my connection to the industry’s history, because he was one of its pioneers. After our lunches, I would go back to my desk and scrawl down everything that I could remember about our conversations onto the pages of these yellow legal pads. I’ve been going through them this past year, with the eye toward a Tuesdays with Morrie-type project. We’ll see. Here’s a good example: “There’s no problem a good book can’t solve.” Without question, Ian was instrumental in my career.

paperback publishing. I was fortunate to get to know Ian well, and would help him out with various favors (mailing packages, research, that sort of thing). In exchange, Ian would take me to lunch at the Top of the Sixes every month, and that’s when publishing became real to me. He was my connection to the industry’s history, because he was one of its pioneers. After our lunches, I would go back to my desk and scrawl down everything that I could remember about our conversations onto the pages of these yellow legal pads. I’ve been going through them this past year, with the eye toward a Tuesdays with Morrie-type project. We’ll see. Here’s a good example: “There’s no problem a good book can’t solve.” Without question, Ian was instrumental in my career.

Each job builds from the one that came before, but it was when I was at Bantam that I came into my own as an editor. Mel Brooks tells a story about when he was writing for Your Show of Shows. His mother was worried about how he would support himself, and even though he reassured her he was fine and that he was getting paid a regular salary, she asked: “They don’t know? You’re OK? They haven’t found out about you yet?” As if he wasn’t worthy and would inevitably be fired. I didn’t get any of that from my Jewish family, but in those early years I did feel a lot like George Costanza at Vandelay Industries. If we’re honest, we all have that self-doubt, but I was so busy at Bantam. I didn’t have time to think about it one way or the other. The next thing I knew, it was like that line in the Talking Heads song, “How did I get here?”

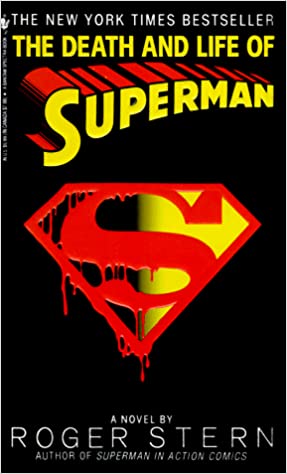

Six years later, in 1993, I was recruited to work at DC  Comics and MAD magazine as the first editor of Licensed Publishing. From there, my career exploded. I worked on some amazing books (including our first New York Times bestseller with The Death and Life of Superman by Roger Stern),

Comics and MAD magazine as the first editor of Licensed Publishing. From there, my career exploded. I worked on some amazing books (including our first New York Times bestseller with The Death and Life of Superman by Roger Stern),

), and I got to meet the most incredible editors and creators in the business (I won’t mention any in particular because I will inevitably leave someone out and insult them). But all of this laid the groundwork for everything I do now in comics.

The books I worked on there were not published by DC. Instead they were licensed to other publishers, and were packaged for publication. As a result, I got to work with pretty much every publishing house in the business, and meet so many other editors throughout the industry. In fact, it was while I was working on a book for Abrams that I was asked if I would like to join them and help develop more commercial projects for the company, which had a new CEO and was looking to reinvent itself. So, after twelve years at DC Comics and MAD, I went to work at Abrams Books in 2005. The rest, as they say (and in the interest of making this as succinct as possible), is history.

Many folks who have not worked in books really don’t know what an editor does. The perception is that editors maybe guide the written words, but there is so much more to it than that. Can you give us a breakdown of an editor’s role in the illustrative storytelling process?

There’s a great story about the Marx Brothers, when they were making the movie A Night at the Opera. They had just signed with MGM, and Irving Thalberg had taken them under his wing and was going to help them break out and be more commercial. I’m paraphrasing here, but one day they were meeting with the director, Sam Wood, and he was going over the script with Groucho and Chico, explaining who their characters would be and what their reason was for being in the film, which was something that Thalberg felt was missing from their earlier films. When they were done Harpo asked, “What about me? What’s my motivation?” To which Wood answered, “You—you run around picking up spit off the carpet.” I think that pretty much sums up the job of an editor better than anything. Actually, a more apt description of an editor is that we are like the guy on the old Ed Sullivan show, spinning plates. Our job is to keep them spinning and not have them fall to the ground and crash all around us.

In reality, the job of an editor is like being a director on a film. You put together the team and all of the various creators (the writer, the artist, the letterer, the colorist, the designer) and you make sure that the final book comes together as you and the writer envisioned it. An editor is not the writer—our names are not on the front cover—but the editor is the one who advocates for the book and is its champion. I remember when I was first editing kids books, someone asked me how long it would take before I would move up to editing adult books, as if it worked that way. Another question I get is when am I going to write my own book. But no one ever asked Alfred Hitchcock when he was going to star in a movie. Being an editor is the job. It’s not a stepping-stone to another position. In fact, those editors I know who have gotten promoted end up being managers and get further and further away from the actual role of making books, which is what attracted them to publishing in the first place.

The reality is that the actual editing of a book—the line editing of the words—is just one small part of the actual job of being an editor. The process is more complicated than your readers would care to hear about. But essentially, in addition to putting together the team, you work with the designer and the art director; you liaise with managing editorial and production; and then, once you hand the book in it’s literally out of your hands. The rest of the publishing team takes over—marketing, publicity, and sales all own the book and take it from there. Publishing is truly collaborative, and no editor, despite his or her vision, is wholly responsible for a book’s success (or its failure to reach its intended audience). In some way, shape, or form, pretty much everyone in the company has a hand in each book we publish, and that includes our contracts department, our royalty department, our inventory managers, and the mailroom. Along the way there’s lots of feedback and course-correcting via editorial meetings, cover meetings, and sales conferences, all of which gets synthesized through the editor. Stephen King once said that, “When you write a book, you spend day after day scanning and identifying the trees. When you’re done, you have to step back and look at the forest.” I think that pretty much sums up the job of an editor, too.

One of the reasons I am excited to have you as one of our judges is that I appreciate your love of comics, for which we have a couple of categories in our competition. You have put together some incredible, definitive monographs on the work of Rube Goldberg, Charles M. Schulz, Jack Kirby, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, Jules Feiffer, Alex Ross, the animated Batman television show, and even more that I’m sure I’m not aware. Where did this love and encyclopedic knowledge of the genre come from?

I have always been curious about the etymology of things. Even as a kid, I wanted to understand the context for what I read or the shows and movies I watched on TV or the music I listened to. If I was into something, then I fell into a rabbit hole, going to the library (there was no internet then) and read everything on the subjects that interested me, writing down in these notebooks complete bibliographies or filmographies or discographies, tracking down everything I could  find. I still have those notebooks, too. So I guess you could say I have always been driven by curiosity.

find. I still have those notebooks, too. So I guess you could say I have always been driven by curiosity.

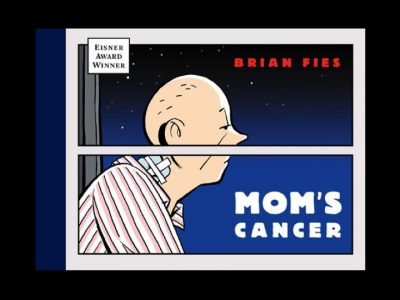

When I came to Abrams, I didn’t come with the intent to publish comics. In fact, after twelve years at DC Comics and MAD, I was looking forward to working on other kinds of subject matter and flexing different editorial muscles. But as I was editing various books on art and photography that had been assigned to me by my publisher, comics kept coming up in conversation or across my desk in different ways, starting with an unsolicited manuscript by Brian Fies for a book called Mom’s Cancer. One by one I started acquiring titles that had this visual commonality to them, so it made sense to create an imprint and gather them together onto one list, which became Abrams ComicArts.

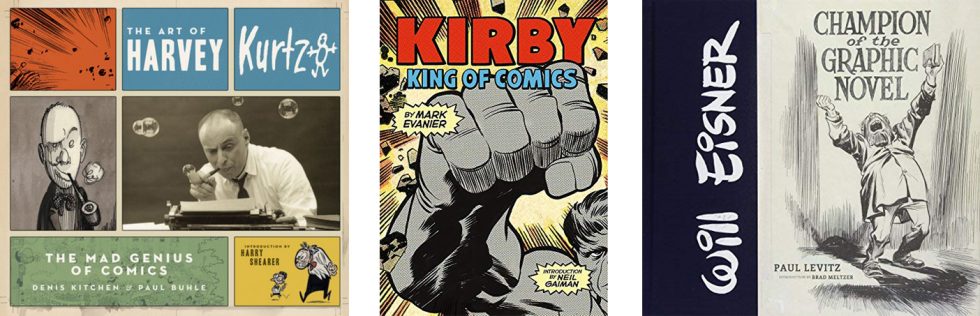

Because the DNA of Abrams is that of an art book publisher, I have always taken seriously the artists who are published on the ComicArts list. So the first thing I did was identify those creators I felt transcended comics, whose work could easily sit on the same shelf alongside the other artists Abrams published, like Rockwell and Picasso. The first thing I did was to come up with a trinity, as I saw them: Jack Kirby (for superhero comics),  Harvey Kurtzman (for humor and his war comics), and Will Eisner (for the graphic novel and the idea of personal expression in comics).

Harvey Kurtzman (for humor and his war comics), and Will Eisner (for the graphic novel and the idea of personal expression in comics).

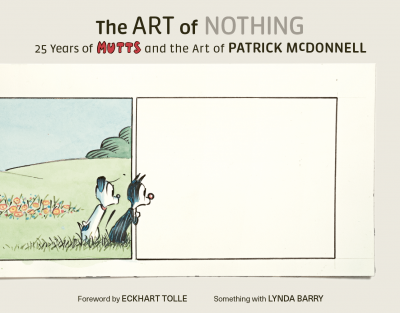

I felt confident that most other creators could be traced to those three in some way, and I consulted with quite a few historians and creators like Paul Levitz, Art Spiegelman, and Jules Feiffer, to make sure my list held up to scrutiny. Given my relationships, I was able to publish those definitive monographs, working with Mark Evanier on the Kirby book, Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle on Kurtzman, and Paul Levitz on Eisner. From there, other monographs followed like the ones you mention above, as well as ones on more contemporary creators like Dan Clowes, Jaime Hernandez, and Patrick McDonnell. There are a few more in the works, too. The trick is to choose subjects who bring something to their art that goes beyond the halls of a comic book convention and can be appreciated by a larger audience.

I think it’s also important to provide context. A monograph can’t just be a collection of images. The reader needs a complete experience, so the book should provide timelines and bibliographies and deep captions and sources—all with the goal of being definitive. Chip Kidd, the graphic designer, says that every aspect of a book is part of the story you are telling. So if you look at those books I’ve mentioned, we try and reward the reader’s experience by giving thought into each and every detail—not just the front cover, but the spine, the flaps, and the endpapers (the front ends are always different than the back because they can be, as Chip says. Their function is the same, which is to adhere the pages of the book to its cover. But a reader approaches a book differently when they open it than when they close it, so there needs to be some kind of juxtaposition or framing between the front and back endpaper images. It’s another part of the storytelling). There is also the case (the images under the jacket), and of course the front and back matter and the overall design itself. When done right, all of these aspects of a book work in tandem and serve to tell the author/artist’s story.

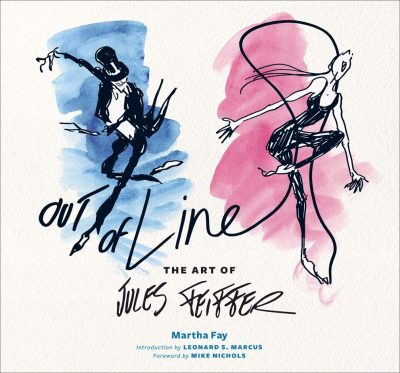

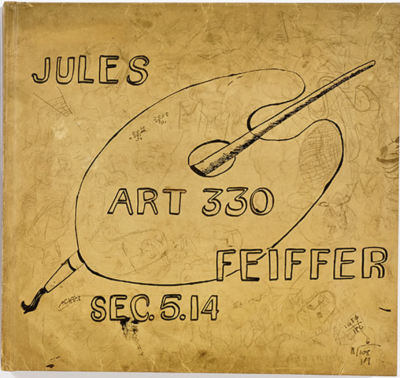

Here’s a quick example that will help to drive this point home: Working with Jules Feiffer on the book Out of Line was a very special experience for a myriad of reasons. First, The Phantom Tollbooth was my favorite book as a kid growing up.

Over the years Jules and I got to become friends, so much so that he initially asked me to write the book. But when I came on staff at Abrams, I couldn’t write the book that I was also going to be editing, so we chose another writer, Martha Fay, who did a terrific job (better than I ever could). Jules attributes me with coming up with the title one night over dinner, and it’s possible. It’s always hard to say who came up with what because ideas are tossed back and forth and one thing always leads to another, so significant details like a title never happen in a vacuum. But we liked the multiple meaning of the phrase, and once we landed on that title, the rest of the book and the design fell in place. We carried his line on the front cover over onto the front endpapers and through the front matter, then had it return at the end of the book and onto the rear endpapers, all of which helped to unify the design and the book’s contents.

Another detail that underscores this idea is the image under the jacket, which is a photograph of Jules’s high school portfolio. I remember showing him the mock-up of the design, and at first he was confused by the idea of a case image. (He had never given much thought to what was under the jacket of any of his books, which were usually just a solid color chosen by an art director). He also wasn’t sure about the image itself, and wondered why I bothered to photograph it in the first place. But when he saw the dummy that we had made, he smiled and said, “I love how unexpected this is. A complete juxtaposition to the elegance of the cover. It’s like my entire career is bookended by this portfolio I schlepped to career is bookended by this portfolio I schlepped to and from school every day. I never would have thought to do that, but it’s genius.”

cover. It’s like my entire career is bookended by this portfolio I schlepped to career is bookended by this portfolio I schlepped to and from school every day. I never would have thought to do that, but it’s genius.”

Well, it doesn’t get any better than that. Most of the monographs I have done, the creators are not around, and you have no sense of how they would have felt about the job you did in presenting their work. That validation from Jules is the reason you go the extra mile, and why you trust that readers will notice, or at least feel the consideration you have given to the object that they are holding in their hands.

I know your love for comics stretches into your appreciation and friendship with many cartoonists. Earlier this year, we lost the great illustrator Mort Drucker (known for his caricature work in MAD Magazine, TIME Magazine, movie posters, etc.) who you were close friends with. Would you care to say any words about Mort?

The single most challenging part of this year is not the isolation, which is difficult, no question. But the hardest part is all of the people we have lost and not having a chance to grieve properly. Mort was a dear friend, and I don’t use the word “friend” lightly, which a lot of people do after meeting someone a few times. Because of my time at MAD, I got to know most of the Usual Gang of Idiots when I was editing the MAD Books imprint. These were all guys I grew up reading, like Al Jaffee, Sergio Aragonés, Angelo Torres, and Frank Jacobs. But it was MAD editor Nick Meglin who took me under his wing, and who is most responsible for helping me forge my relationships in the industry. Nick pushed me to join the National Cartoonist Society, and it was through the NCS that I got to spend real time with so many of my childhood heroes, all of whom Nick was friends with. And because  Nick and I were such close friends, whatever plans he made he always invited me along. In fact, he even invited me along on a blind date once (they didn’t hit it off, but she and I did, and to this day she is like my adoptive mother).

Nick and I were such close friends, whatever plans he made he always invited me along. In fact, he even invited me along on a blind date once (they didn’t hit it off, but she and I did, and to this day she is like my adoptive mother).

You always hear that you should never meet your heroes because you will only be disappointed, but that adage doesn’t apply to comics, at least in my experience. And it certainly doesn’t apply to Mort Drucker, who was everything you wanted him to be and more. Mort could not have been nicer, more encouraging, or more paternal to me and to my wife. He even came to our wedding, and it made so me happy to see my brother sitting at a table with Mort and the MAD guys talking well into the night. After it was over, Mort gave my brother a lift to his hotel, which—despite the occasion—my brother said was one of the highlights of his life. I take no offense at that, because I know exactly what he meant. Mort was welcoming and generous, and all that is apart from his talent as an artist.

I am sorry we have not had a chance to gather and celebrate him, but I am in touch with the family and we are talking about a proper memorial when the world is back to normal. There’s a lot that needs to be said and shared about Mort Drucker, and I look forward to commiserating with others and celebrating him with those who feel the same way. He deserves it.

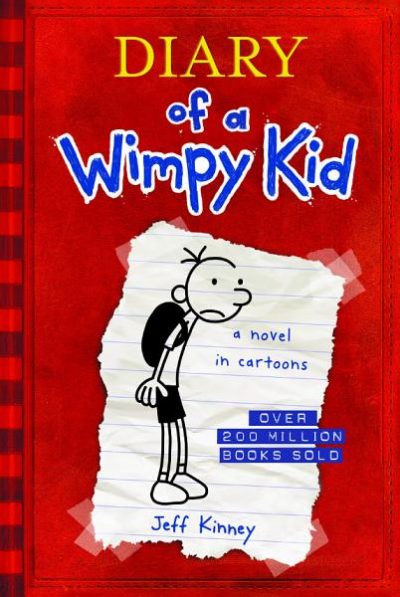

Today, children and their parents everywhere are aware of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid franchise that you shepherded, but when a project first comes along to a publisher, no one has the expectation that it will lead to many books, movies, and balloons in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. What did you see in Jeff Kinney’s pitch that first time you laid eyes on the project?

If there’s one thing I know for certain will be a part of my obituary, it’s that I am the editor of the Wimpy Kid books, and I am more than OK with that. When I met Jeff Kinney at the first New York Comic Con in 2006, I had no idea that we would sell over 250 million copies of his books and travel the world together. I just knew I liked what he showed me. Truthfully, that has always been what guides me. Editors are proxies for the reader, and I felt immediately that I wished I had had something like Wimpy Kid when I was growing up. The idea of a brief amount of text (which is the setup) followed by an image (the punchline) was instantly appealing to me.

Although I read a lot as a kid, I was definitely a reluctant reader, and gravitated to comics because of the artwork. When I read novels, I would read to the picture, overwhelmed by the amount of text before me. Jeff describes those single-page images as little islands that he would swim to, and I know exactly what he means. They were one less page you had to read—a reward for getting through one more passage or chapter. In Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Jeff solved the problem of overwhelming reluctant readers.  His format has now been copied ad infinitum, but at the time it was radical.

His format has now been copied ad infinitum, but at the time it was radical.

It was neither a chapter book nor a comic, therefore it was “nothing,” as someone told me back then. But my background was in children’s books, and I also had the other foot in licensing and in comics. And Wimpy Kid checked all of those boxes. Fortunately, I saw something that others didn’t—the empty space between books on the shelves that my uncle Burt was telling me about.

At first Jeff was not conceiving of this as a book for kids, but rather like the Wonder Years—an adult looking back at his childhood. But when I brought the book to our editorial meeting, no one saw what I saw. Instead of giving up, I pivoted—there was no reason this could not be a book for kids, I felt. So I shared the proposal with the team in the children’s book department, and thankfully they saw what I saw in Jeff’s work and were equally enthusiastic. There’s always a little revisionist history when something becomes successful, but the moment of making this a children’s book series is the moment that Malcolm Gladwell talks about in Outliers: “The Tipping Point.” And that moment, along with my meeting Jeff, are very much etched into my memory given how profound they were, and because of the steps I had taken leading up to that decision.

It’s important to keep in mind that at the outset, Wimpy Kid was never a lead title at Abrams. None of us, myself included, ever envisioned it would go on to be the success it has become. You can’t really plan these things, they just have to happen organically. Some of those involved in the process of bookmaking like to talk about publishing like it’s a science, but publishing is really a combination of alchemy and timing. If we knew how to replicate success, we would all do it.

It’s hard to believe that we’ve just released the fifteenth book in the series (and that doesn’t include all of the ancillary ones we’ve also done together). It’s gratifying to know that kids all over the world have become readers because of Wimpy Kid. Now, here we are fourteen years later. To still be working with Jeff on the series and to have become close friends in the process—it really is an honor and the single greatest achievement I could hope for when I set out to be an editor.

Editors always have multiple projects in various stages of development at any given time. What can we expect to see in stores soon from the desk of Charles Kochman?

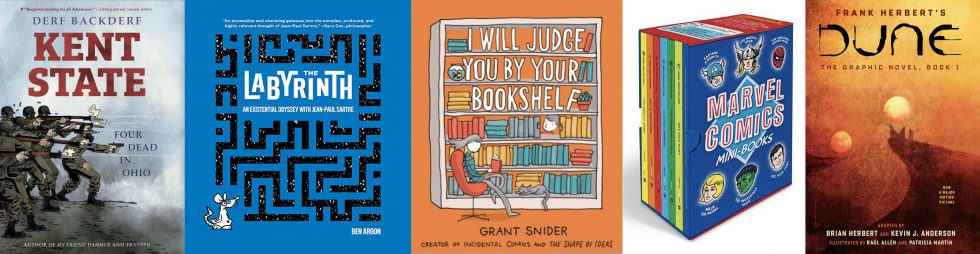

Thanks for asking. I feel like a lot of good books came out this year, but because of the pandemic, they didn’t get the attention they would have otherwise received—titles like Kent State by Derf Backderf, The Labyrinth by Ben Argon, I Will Judge You by Your Bookshelf by Grant Snider, and Marvel Comics Mini-Books by Mark Evanier.

In terms of what’s coming up, be on the lookout for the graphic novel adaptation of Dune, as well as Run: Book One by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin. I am sorry Mr. Lewis will not be around to help us celebrate his legacy with that book, but I am confident we have done him justice, and I am glad he was able to see the final pages before he passed.

Those are the projects on the immediate horizon, but I ask for forgiveness from any authors I have left off this list. I am not one to play favorites—I just know that a long list will be less effective than highlighting a few.

Are there any books you wished to publish that you weren’t able to publish for one reason or another?

Good question. There are always the ones that get away, but honestly, no, I can’t think of any off the top of my head. Editors get pitched way more books that we could ever publish. And our wish list of books we want to publish is longer than we will ever hope to achieve. There are always books you lose out to another editor at another house. But I tend not to think about a book once it is no longer a possibility. Some books you never hear about again once you lose them. Those that you do hear about, the ones that go on to be successful—well, there’s no guarantee you would have had the same success had you published it. In most cases, the book found the editor it needed or the home it deserved.

I have heard, over the years, from a handful of writers who circled back and said with regret that they wished they had signed with me and Abrams. That’s flattering and all, but it’s hard to look back because of what is on my plate at the moment. We publish our books in two seasons: Spring and Fall. And each season there are anywhere from five-to-ten books I am either editing or overseeing. So that doesn’t leave a lot of time for regret.

The other thing to keep in mind is that comics publishing is a very small industry. So, by and large, I know my counterparts at most of the other houses. We’re all friends, and we all genuinely like one another and are fans of the books that are being published at this moment in time. Each of us grew up reading comics, and now we get to work on them—which is pretty remarkable when you think about it. And besides, there are more than enough books to go around. The important thing is that the books we publish succeed. You know the saying, “A rising tide lifts all boats”? In comics, each book that raises its head above the water helps not just the company that publishes it, but all of us who publish comics.

Back when we could eat dinner indoors and see other people, I would regularly get together before a convention with some of the other editors and we would raise our glasses. It felt like the head of the Five Families were gathered, only there was no grand plotting or divvying up of territory. Just comradery and celebration, and we wanted to take the time to enjoy what we are doing, because it’s really special and it’s important not to lose sight of that.

Thanks so much for being one of our judges this year! Here’s hoping we shall see an exciting array of entries from artists around the globe!

Thank you, Chad. I look forward to seeing the entries as well. I’ve always felt that it’s one thing to publish books with established creators, but the most fulfilling part of my job as an editor is discovering new artists and looking at work that may not be new, but new to me. I look forward to seeing the submissions and am honored to be in the company of such an esteemed jury. Thank you, my friend.